It really is a very odd business that all of us, to varying degrees, have music in our heads. When the Overlords of Arthur C. Clarke landed on our planet, they were surprised by the energy that our species applied to producing and listening to music; they would be even more surprised to learn that, even in the absence of external sources of stimulation, we hear for the most part continuous interior music. (Oliver Sacks, Musicophilia)

Whether we want to be or not, we are all science-fiction characters living in a science-fiction period. (Ray Bradbury)

Bach never modulated in the conventional sense, and leaves the extraordinary impression of an infinitely expanding Universe. (Glenn Gould)

Before we begin to imagine the natural and unnatural copulations between music and science-fiction, perhaps it’s best to define the latter, which is often for some what it is not for others, and not necessarily vice-versa.

In the 1950s, Jacques Sternberg titled one of his works: A Subsidiary of Fantasy called Science-Fiction. A bit simplistic, perhaps. Especially considering that fantasy is a non-rational novelistic conjecture, which squarely places it in a different conceptual niche from science-fiction, which is considered “more or less” rational. Pierre Versins, author of a now-mythical Encyclopedia published in the early 1970s, believes that science-fiction is a universe that is bigger than the known universe. A bit excessive, however. Versins must have realized as much, because he later specified: Science-fiction is not a “literary genre” but a state of mind (…) which is revealed through all genres, from poetry to film, and in all forms, from image to discourse.

This is where it gets much more interesting. Norman Spinrad, author of cult books Bug Jack Barron and The Iron Dream, hammers in the nail: We can only define science-fiction by the perception we have of it. Science-fiction is therefore what is perceived as such. So there is no doubt that Gravity’s Rainbow (Thomas Pynchon), House of Leaves (Mark Danielewski), Glamorama (Bret Easton Ellis) or Mantra (Rodrigo Fresan), while not publicized as such, can be perceived as science-fiction novels, just as Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly), Element of Crime (Lars Von Trier) or Mulholland Drive (David Lynch) can be perceived as films of the same genre.

What about music?

Since at least the 18th century, music has tapped into the world of science-fiction. One of the first musical works to be assimilated with SF is probably Joseph Haydn’s opera Il mondo della luna (1777), with a libretto by Goldoni, in which a truant tricks a gullible astronomer into believing that he lives on the moon. Later, Leos Janacek also takes an interest in our satellite with The Excursions of Mr. Broucek (1917), who first visits the moon and then time-travels to the 15th century. The science-fiction opera has tempted numerous neo-classical or post modern composers, such as Lorin Maazel (1984, based on George Orwell’s novel), Philip Glass (The Making of the Representative for Planet 8, based on a libretto by Doris Lessing) and Howard Shore (The Fly, based on George Langelaan’s short story and directed by David Cronenberg).

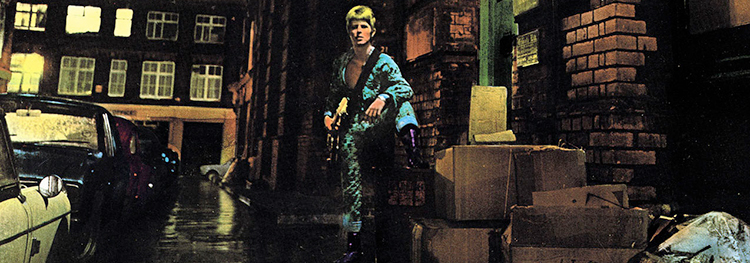

The worlds of jazz and especially rock, which are part of the same cultural, or rather counter-cultural community, as Boris Vian, Philip K. Dick, Robert Silverberg, Philip José Farmer, Michael Moorcock and J.G. Ballard, have more naturally built a number of bridges with SF. One of the most assiduous is David Bowie, with an imposing number of works, including Space Oddity (1969) inspired by 2001, a Space Odyssey by Arthur C. Clarke, or the concept album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders of Mars, which narrates the escapades of an extraterrestrial rock star, and Diamond Dogs, a dystopia in the spirit of 1984.

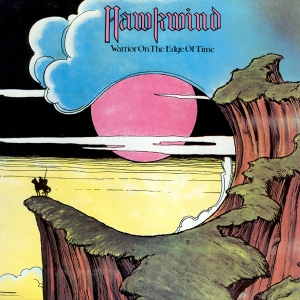

We could list dozens of groups, of course, but that deserves an article of its own (1). However, we will mention the British group Hawkwind, almost all of whose albums fall under the sign of SF, including Warrior of the Edge of Time based on the Cycle of the Eternal Hero by Michael Moorcock (who wrote the lyrics to three of the songs on the album), and the French group Magma, whose entire production revolves around the relationships/conflicts between Earthlings and the planet Kobaïa (with lyrics written in the ad hoc invented language of Kobaïan).

But psychedelic music is where SF has most potential in the Spinrad sense of perception. First off, there is the Pink Floyd spaceship piloted by Syd Barrett who delivers titles sparkling with stars and scented with acid and marijuana, such as Astronomy Domine, Interstellar Overdrive and Set the Control for the Heart of the Sun, as well as the whole “Krautrock” constellation (German rock of the 1960s and ’70s) with the representatives of the “cosmiche musik” trend: Tangerine Dream (Alpha Centauri, Phaedra, Rubycon, Stratosfear) or Klaus Schultze (Cyborg, Timewind, Moondawn, Dune), whose album titles evoke interstellar cargo-crossed immensities and more or less exotic planets that were already celebrated by Gustave Holst in his time. But whereas the British composer’s music only fully functioned as illustration once the theme was announced, all it took was a few notes for the cosmiche rockers to propel us into space.

But psychedelic music is where SF has most potential in the Spinrad sense of perception. First off, there is the Pink Floyd spaceship piloted by Syd Barrett who delivers titles sparkling with stars and scented with acid and marijuana, such as Astronomy Domine, Interstellar Overdrive and Set the Control for the Heart of the Sun, as well as the whole “Krautrock” constellation (German rock of the 1960s and ’70s) with the representatives of the “cosmiche musik” trend: Tangerine Dream (Alpha Centauri, Phaedra, Rubycon, Stratosfear) or Klaus Schultze (Cyborg, Timewind, Moondawn, Dune), whose album titles evoke interstellar cargo-crossed immensities and more or less exotic planets that were already celebrated by Gustave Holst in his time. But whereas the British composer’s music only fully functioned as illustration once the theme was announced, all it took was a few notes for the cosmiche rockers to propel us into space.

How is this exploit possible without the use of words or images to funnel the listener’s imagination? With David Bowie or Hawkwind, the SF perspective is also suggested by the texts and imagery on the album covers. But without these textual or visual references, their music is incapable of assuring that the listener’s imagination is oriented toward science-fictional worlds. Hence the question:

Does science-fiction music exist?

Referring to Spinrad’s definition, I believe that we can answer in the affirmative: Phaedra, Rubycon, Moondawn, Dune, and almost all the German psychedelic albums that “sound” sci-fi, and which can therefore be considered as SF music. This leads to another question, which is much more difficult to answer:

Why—or rather how—does certain music sound sci-fi?

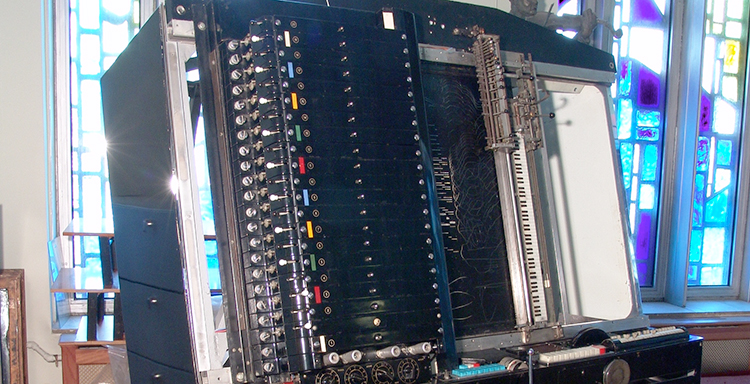

The archetypes of science-fiction, such as time machines, teleporting machines or space machines stuffed with electronics must have something to do with it. Indeed, sequencers, drum machines, samplers and, of course, computers decked music software are no longer instruments but also “machines” that generate sound. In the first half of the 20th century, they were only pure “anticipation”, excepting the first creation of mad engineers: the telharmonium (1900) or ætherophone (1919), better known as the Theremin, which already smelled like steampunk.

These first electronic instruments were often used before the arrival of synthesizers to add a certain “strangeness” to the soundtracks of fantasy and science-fiction films. The same can be said about Ondes Martenot (1928), the ingenious “steampunk” ancestor of the synthesizer, with its wooden keyboard and portable electronics. The German group Kraftwerk (who use the Ondéa, the modern version of Ondes Martenot) has played on these archetypes with the most clairvoyance and efficiency, especially on stage: electronic music + minimalist texts made up of keywords interwoven like strands of DNA + “hard science” stage design with robots standing in for the musicians + projection of films on key topics of science and technology… Thus, they are undeniably the precurseurs of cyberpunk (2). While their cosmiche colleagues ogled the space opera, albeit as sophisticated as Dune (inspired by Frank Herbert’s novel), Kraftwerk build a bridge between William Burroughs (Naked Lunch, Nova Express) and J.G. Ballard (Atrocity Exhibition, Crash) on one hand, and William Gibson (Johnny Mnemonic, Neuromancer) and Bruce Sterling (Mozart in Mirrorshades, Schismatrix), the popes of cyberpunk, on the other.

But synthetic sounds alone do not trigger a mental cinema in the image of space opera or even cyberpunk. The “composition”, the creative talent of the musician (fortunately) remains an essential element. As evidence, let’s go back in time for a moment (time travel is still a beautiful invention):

In his Last conversation before the stars, (1982) Philip K. Dick talks about his plans for a new novel titled The Owl in Daylight in which one of the main components is music, saying Pythagorus concluded that the foundation of the universe was the combination of mathematics and music, because they are two aspects of the same thing. Such was his teaching—hence the expression “music of spheres”. Then he said that moving bodies emit music but that we don’t hear it because we’re immersed in it since the time we were born, so we’re no longer aware of it. However, we perceive uninterrupted music.

This music that we do not perceive, but that exists somewhere in the mathematical universe of the world, do we not hear it somehow in the soundtrack of Eraserhead as “interpreted” by David Lynch and Alan Splet? It seems that this reinvented music of matter, of time and of space is, according to Spinrad’s definition, unquestionably science-fiction music, just like the images that go with it.

This music that we do not perceive, but that exists somewhere in the mathematical universe of the world, do we not hear it somehow in the soundtrack of Eraserhead as “interpreted” by David Lynch and Alan Splet? It seems that this reinvented music of matter, of time and of space is, according to Spinrad’s definition, unquestionably science-fiction music, just like the images that go with it.

We can also get an idea of this explicitly SF intention through a creative shock: in the overture of Zaïs, where Jean-Philippe Rameau manages to musically translate the establishment of a progressive order of matter, in a true harmonic interpretation, two centuries ahead of his time, of the evolution (or nucleosynthesis) of interstellar matter (3); or in Les Éléments (1721) by Jean-Féry Rebel, who selects chords and arranges them to express chaos by themselves, without relying on voices or décor. The surprisingly modern result could have been signed by Art Zoyd. Whatever the perspective, on one side of time or the other, from listeners of the era to those of today, the creative shock triggers a break from reality and propels the work into SF.

This “break” is now “common”. We live in a bubble of the expanded, inflated present, lashing out its tentacles in all the senses of time. Accelerated duplication, cloning, drones. Technology is icreasingly overtaking basic research. Electronic music, now digital, lives its own life. It regenerates, metamorphoses, samples and duplicates, lives, dies and rises from its samples. Compression-expansion. The entire history of music in a nanosecond loop. Numbers are numbers.

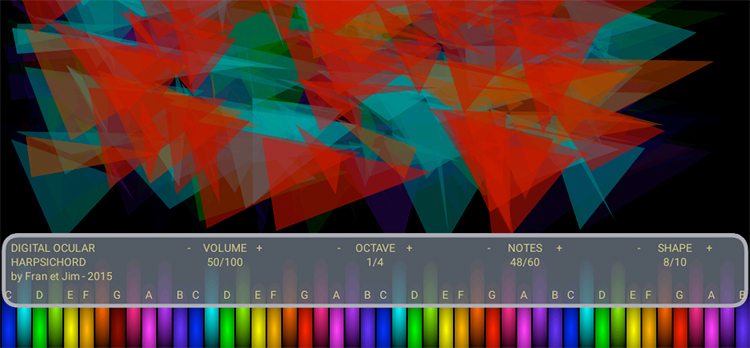

The first time that Philip K. Dick took LSD, he was listening to a quartet by Beethoven, and he saw it in the form of a cactus. With each progression, from measure to measure, the cactus gained complexity; it was a process of accretion, and no longer a succession. It grew bigger and bigger, more and more complex. Through synesthesia, Dick saw Beethoven’s quartet in the form of fractal scaling, a Fibonacci series. He “naturally” converted the sound into image, just as a software program would have done digitally. Probably without knowing it, he was anticipating the digital revolution capable of “dematerializing” sounds and “rematerializing” them as images.

Number are numbers, and today all music is science-fiction.

Jacques Barbéri

published in MCD #70, “Echo / System : music and sound art”, march / may 2013

(1) See, among others, the feature Culture rock & science-fiction (Bifrost 69 magazine, January 2013)

(2) In the same vein (without the electro-pop touch), we can mention the French group Heldon and the solo albums of its leader, Richard Pinhas (to whom we owe an excellent book on Deleuze and music: Les larmes de Nietzsche), precursor in the 1970s of cyber-electro music that openly referenced Philip K. Dick, Norman Spinrad and Michel Jeury.

(3) In Astronomie et musique au siècle des lumières, Dominique Proust.

A writer and musician, Jacques Barbéri has published the trilogy Narcose — La Mémoire du Crime, Le tueur venu du Centaure (La Volte), short story collections, Kosmokrim (Présences du Futur), L’homme qui parlait aux araignées and more recently Le Landau du Rat (La Volte). > www.lewub.com/barberi/

Barbéri is also a member of the group Limite, formed in the mid-1980s with other writers such as Emmanuel Jouanne, Francis Berthelot, Jean-Pierre Vernay and Antoine Volodine, sharing the will to experiment and transgress writing and narrative codes in science-fiction (see the anthology Malgré le monde, Présences du Futur). > www.rumbatraciens.com/limite/mecanique/m002.html

In parallel, Barbéri performs (saxophone, electronics, text) in the group Palo Alto led by Denis Frajerman. The discography of this experimental and atypical group includes Terminal Sidéral (CD+DVD on Optical Sound), Cinq Faux Nids Six Faux Nez with DDAA (Déficit Des Années Antérieures) on the label Le Cluricaun and, of course, Slowing Apocalypse: a tribute to J.G. Ballard published by È®e, featuring Laurent Pernice, with whom Barbéri also recorded Drosophiles & Doryphores, an electronica and melodic album on the multimedia Slovenian label rx:tx.