there is no predicate « this is literature »

Several times in your texts, you emphasize the strength of the ecosystem of reading. As a publisher, how do you feel our digital environment has changed our relationship with reading?

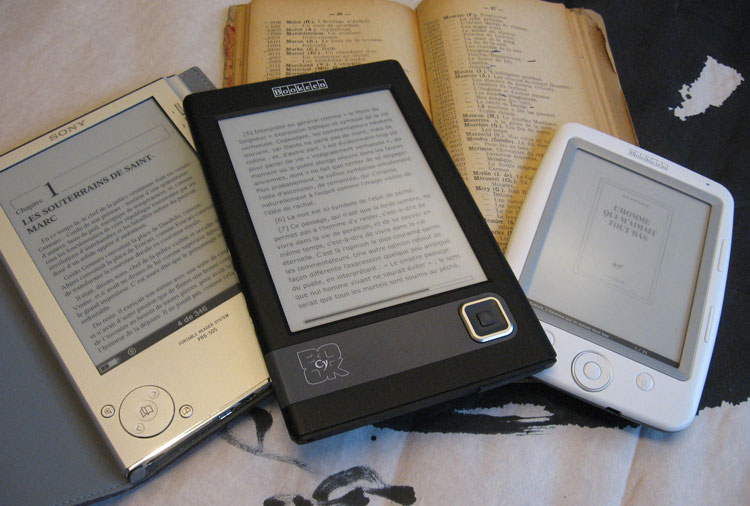

I’ve been working with texts in digital format almost since I’ve had a computer, in 1988. But it was a work relationship. The first e-readers (for me, the Sony, in 2008) allowed us to read continuous prose as comfortably as a paper book. But the ergonomics weren’t really perfected yet. Now, both because we know how to make epubs that are comfortable and stable (more or less the same on any reading device) and because the devices themselves have evolved, we can forget about them. You have it in your pocket, you don’t think about going to buy a newspaper or a paper book anymore. The iPad became the first companion for personal reading, but since the recent arrival of the Odyssey, the Kobo, I’ve gone back to reading on dedicated e-readers. These devices are good, because now we forget them—it’s paper books that we find annoying, when we have to shlep one around, or when we have the reflex to click on a word with our finger to call up the dictionary or the search engine.

Again, as a publisher, you strongly oppose DRM. Aren’t you afraid that the same thing will happen to e-books as with music, that is, widespread sharing with free access via P2P (what we commonly call « piracy »)?

Let’s stop using the word « afraid ». I’m afraid to walk down the stairs, so I stay upstairs. It’s not about being afraid of piracy, it’s about continuing to make contemporary literature desirable and demanding. The notion of ecosystem is used in the context of the Internet, where we offer access to our creative studio, and thus to a large free portion of our works. But with e-books—for example, but not only—we can offer a « service », a commodity of access, which can also include shared annotations, updates, expanding works that make peer-to-peer dissuasive or useless.

Liseuses électroniques. Photo: D.R.

Considering the philosophy of access rather than possession, aren’t you afraid that access to books—and therefore to knowledge, culture, art—is concentrated in the hands of companies, which are themselves quite concrete and can disappear from one day to the other, thus depriving readers of access to the texts?

There it is again, the word « afraid »: I’m afraid of Nestlé, so I don’t buy milk for my kids. Yes, we face a centralized distribution system, whose reason for being is far from humanistic. It’s the same for car sellers. But we can tell ourselves, on the contrary, that we invest in them, that we use their tools not only to authorize access to our work, but also to promote it. That’s what we do, and often in dialogue with them. The question is confusing; perennial access has nothing to do with it. The role of libraries, having our own servers complement or mirror those of digital libraries, even if my computer gets run over by a truck, or if Apple stops distributing e-books tomorrow, makes no difference.

Aren’t libraries the guarantee? Meaning that libraries will also have to go through their digital revolution?

Why use the future tense? Fortunately, they didn’t wait for the shockwaves to rethink their profession in digital terms. It still involves the tasks of mediation, orientation, the notion of public service in access (when large university campuses such as Nice, Montpellier or Strasbourg give each connected student integral access to Publie.net). If the librarian’s job were only to index, bind and lend books, what’s the point?

As a writer, in a 2006 interview for Le Magazine Littéraire, you wrote: It’s surprising how much the literary world distrusts the Internet. Do you believe that it’s still true?

It seems evident to me, at least if I compare it with artistic professions such as musicians, or scientific professions (excluding academic literary departments, which are even more behind). Most print writers tend to have the polar bear syndrome, with their claws firmly gripping the melting, drifting glacier. But of course, the environment has changed in the past five years. The authors who have emerged, and who have begun publishing since then, came with their digital habits, their blogs, and they know very well that if you want to know what’s going on, best go online.

In a way, couldn’t we say that the Internet « transpires » through today’s writers? I’m thinking of the recent cases of plagiarism: « Hegemann » in Germany and « Houellebecq » in France?

Those plagiarism cases are nothing but headline fodder for failing newspapers. We always write with what has already been written.

Liseuses électroniques. Photo: D.R.

One of your articles, reprised in your latest work, after the book, is titled (writing) that comments are not writing at the bottom. It’s a beautiful formula. Do you think that comments enrich the text as an integral part of it? In other words, that writing a blog entry is more of a process than a definitive act? Do you think we’re returning to a form of orality in writing?

Literary history, and not just Jewish tradition (like the Zohar), has always included its own commentary, what Maurice Blanchot called « the infinite conversation ». The difference is that reading/writing in one word can now fit on the same device, be perfectly symmetrical in those positions, and intervene before publication, where it’s the construction site itself that is published. We don’t change the collective body of literature, which is also compatible with the « essential solitude » of the author—I’m thinking of the conversations noted by Kafka, the 3,000 letters left by Beckett—but this collective body can go beyond the private sphere, not have to wait for publication as hierarchy.

A question for both the publisher and the writer in you, one that you’ve been asked many times, but I can’t resist: Do you think that the notion of author has evolved under the influence of not only digital publishing but also digital writing?

The notion of author, no. The notion of writer, yes. This term was invented in the 17th century, in the context of a specialized function and what it generated. Over the course of the 19th century, with the commercial development of literature, it gradually gained a more fetichistic or symbolic value. Of course, with the Internet, we start over again at zero.

Now I’m thinking about the art of mixing, appropriation, sharing… Do you think that the notion of authorship has changed with the flow and Web 2.0? In other words, don’t you think that with the Internet, collective writing has become reality?

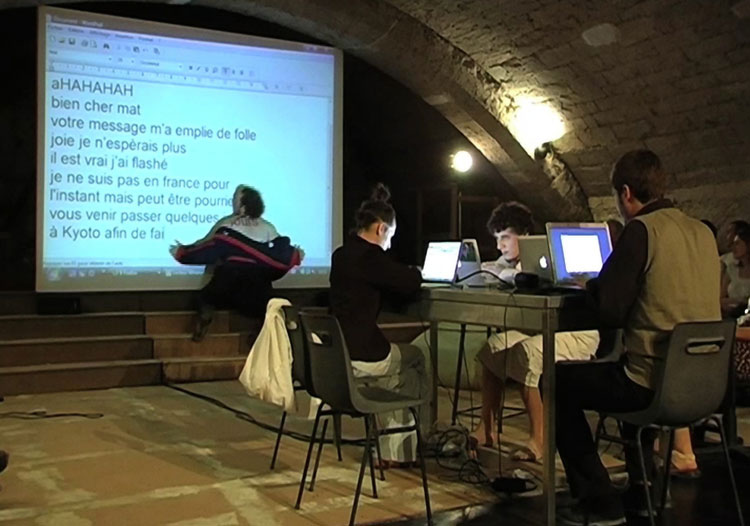

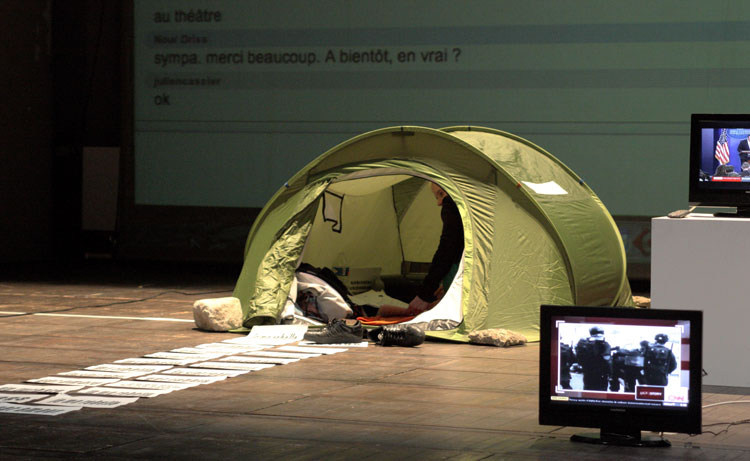

Collective writing didn’t wait for the Internet to become reality. Examples abound, beginning with the surrealist adventure. What is fascinating—and I say this more as a viewer—is to see Web experiments that allow very new forms of collective realization, and that it’s quite compatible with the deep, solitary commitment of those who participate in it.

Do you think that hypermedia literature is literature? Don’t you think that this type of literature suffers from a lack of publishing? Why hasn’t Publie.net done anything about it? Is it an economic problem?

There is no predicate « this is literature ». That’s why we need to constantly verify our assumptions. Neither Madame de Sévigné, nor the bishop Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet, nor Saint-Simon wrote for literature. It’s a constantly retrospective construction. On the other hand, I seriously invite you to come visit Publie.net, as the iPad is a great invention for « hypermedia » experiments—except that, precisely, we don’t need to call them anything so barbaric. We simply call them « books », period.

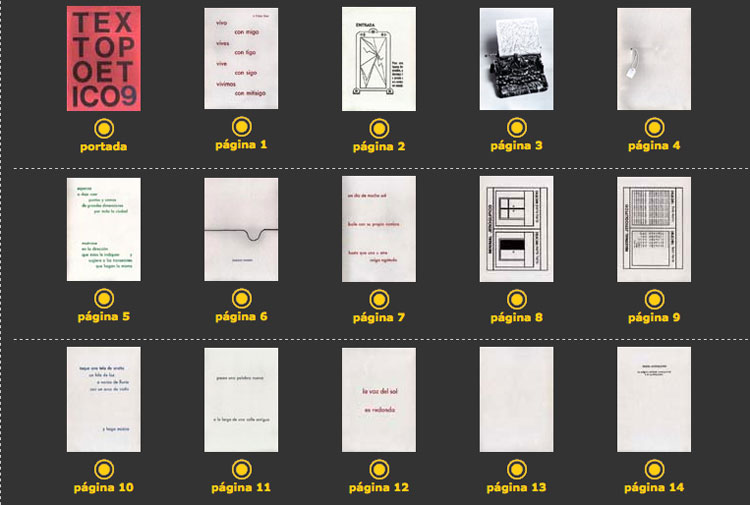

Writers have always integrated their medium (without always questioning it). In France, writers such as Mallarmé and Apollinaire questioned the letter and the page. In American literature, B.S. Johnson cut holes into his Albert Angelo, Douglas Coupland played with fonts and pagination, Mark Danielewski turned the book upside down, etc. In what way is e-publishing a new medium for writers to explore?

You’re a child in front of a candy store. A very serious man asks you the question: In what way is a candy store a new medium for children to explore?

François Bon à la médiathèque de Bagnolet, 2009. Photo: D.R.

Literary and media Friedrich Kittler wrote in 1985: literature, which formerly ruled under the name of poetry above all other media, is now defined by other media. What do you think?

Couldn’t care less. Patter for a professor paid in career points after publication. If that’s the exact sentence, taken out of context, then this guy must not have read a whole lot.

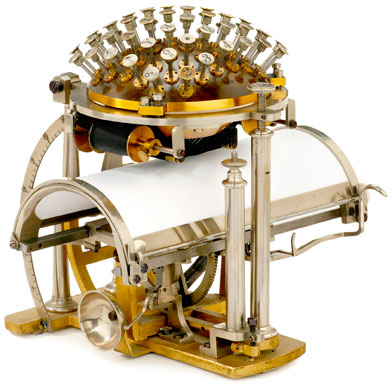

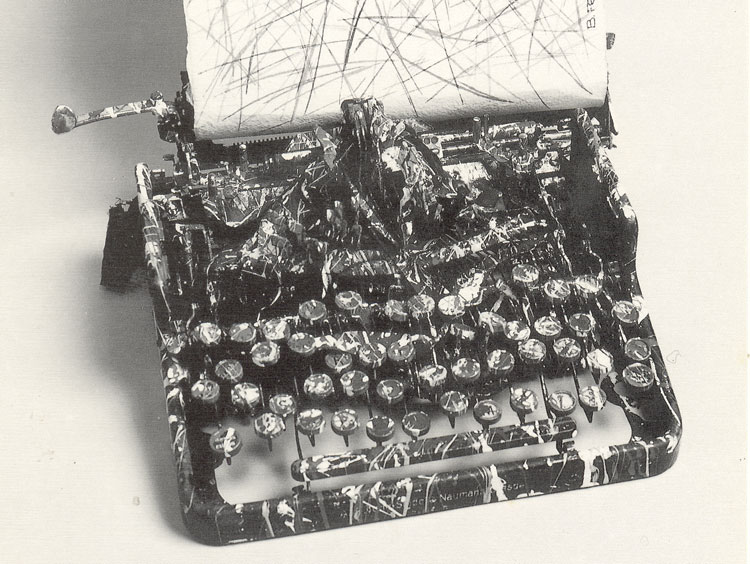

In general, do you think that writing and reading machines (printing, typewriters, PCs and now tablets…) determine the way we write?

No, it’s our head that determines it. And urgency. And the notion of beauty. And the notion of our own experience among others. And our passion in language. And what we make from it.

Bonus question: You are one among that rare breed of writer-publishers. How do the writer and the publisher live together?

It’s the Old World that determines these partitions. They’re very recent. There are dilemmas that are never easy to resolve, for anyone, anywhere, regarding the relationship between work and personal time, including the tunnels, in relation to more collective involvement. Similarly, we don’t read the same way if we’re in the middle of writing something, or in a certain phase of writing. I launched with some friends a digital publishing cooperative, because we vitally needed to experiment, to have our own space for textual invention—including (but not only) because of the inaction or frigid hostility of our own publishers (it’s different now, they smell the cake). But it wasn’t in order to play out an entrepreneurial model, or the paternalism of publishing houses that we had known, or even the « economic models » and other bullshit. Writing is intransitive, said Maurice Blanchot. Let’s assume this intransitivity where we « already » have our territory for reading, writing and experiencing the world: online.

Interview by Emmanuel Guez

published in MCD #76, “Writing Machines”, march/may 2012/p>

François Bon: www.tierslivre.net

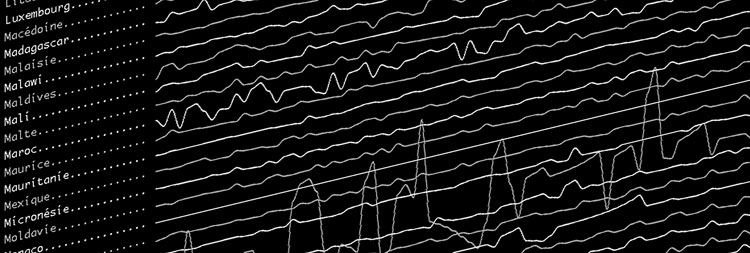

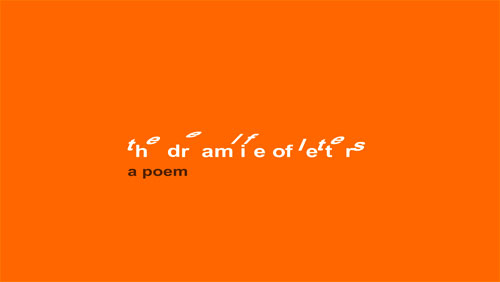

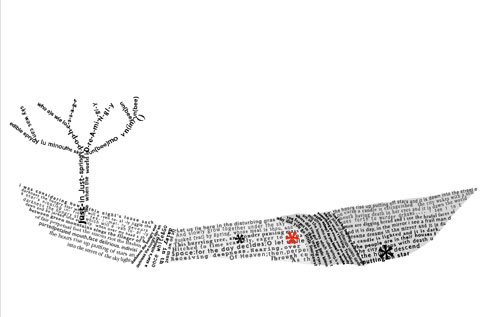

To wrap up, a word on QR (Quick Response) codes, those two-dimensional bar codes that pop up everywhere, on all kinds of ads and political campaign posters. QR (under free license) can be read by any last-generation mobile phone. Encapsulating texts, sounds and images, QR are a new format and a new medium for poets who love to play with the material aspects of writing. Putting a poem into a QR is playing with your own invisibility. In France, there have been a few rare attempts of varying interest (by Stéphane Bataillon, for example). With his background in graphic design, the American artist Peter Ciccariello takes the game farther by placing a QR (containing a poem and a first image) into a second image, which is generated by a computer. Facinated by the relationship between words and images, Ciccariello produces visual artworks that usually include poems which have become almost unreadable in linear form, as a result of their insertion in sophisticated collages esthetically reminiscent of the 1980s and ’90s. In QR Poem, the artist reiterates Mallarmé’s gesture of randomness, generating poems that are decrypted and de(QR-)coded rather than interpreted… Or how, with a roll of the dice, to write a poem using technology that was initially designed to manage your stocks!

To wrap up, a word on QR (Quick Response) codes, those two-dimensional bar codes that pop up everywhere, on all kinds of ads and political campaign posters. QR (under free license) can be read by any last-generation mobile phone. Encapsulating texts, sounds and images, QR are a new format and a new medium for poets who love to play with the material aspects of writing. Putting a poem into a QR is playing with your own invisibility. In France, there have been a few rare attempts of varying interest (by Stéphane Bataillon, for example). With his background in graphic design, the American artist Peter Ciccariello takes the game farther by placing a QR (containing a poem and a first image) into a second image, which is generated by a computer. Facinated by the relationship between words and images, Ciccariello produces visual artworks that usually include poems which have become almost unreadable in linear form, as a result of their insertion in sophisticated collages esthetically reminiscent of the 1980s and ’90s. In QR Poem, the artist reiterates Mallarmé’s gesture of randomness, generating poems that are decrypted and de(QR-)coded rather than interpreted… Or how, with a roll of the dice, to write a poem using technology that was initially designed to manage your stocks!