Subject: Re : interview questions

Date : Saturday, December 3, 2011 00:43

From: Jean-Pierre Balpe <xxxxx@gmail.com>

To : emmanuel guez <xxxxx@yahoo.fr>

Jean-Pierre Balpe ou les Lettres Dérangées, 2005. Photo: D.R.

You’re one of the pioneers of world electronic literature. It still remains relatively unknown to the general public. Why?

Literature doesn’t really exist outside of the institutions that commercialize it, vulgarize it, teach it, defend it, promote it, etc. Electronic literature is an orphan in this case, as it doesn’t fall within traditional institutional channels. The rise in power of e-readers could have changed this situation, except that they were taken over by book institutions in an almost caricatural way—an Amazon Kindle buyer, for example, can only order from Amazon. Moreover, these institutions, which are all directed by staff with conventional training, not only don’t know what to do with electronic literature, they don’t even know that it exists. Anyway, the « general public » is only interested in bad literature, the kind that sells and corresponds to the selection criteria of established literary institutions. But in the end, it doesn’t really matter…

In regards to generative writing, where does the writer’s work come in? During the coding? In this case, isn’t it more about rhetoric than poetry?

No matter how automated, there is no literature without a writer, that is to say, without an author determining the rules, defining the world and piloting the programming. Only, this writer’s job is more than that, he’s what I call a « meta-author », an author who analyzes his writing desires in order to create models and exploit them with a computer. I don’t see how this is about the difference between rhetoric and poetry; these two elements, if there really is a difference, have so far only served people trying to analyze texts by extracting relatively abstract concepts. Programming texts is not at all based on these approaches, which aren’t practical. For example, the notion of « metaphor » allows us to describe manipulations in the language of the texts, but it doesn’t say anything about how to program these manipulations, because it’s on a level that’s too general and non-operative. Generating texts must rely on other, radically different approaches. Similarly, the notion of grammar, which seems so important in describing languages, doesn’t in any way inform a programming approach. As to the coding, it only represents one level of the programming approach, which is actually independent of any one programming language. The code is a restrictive tool, but it only plays a small part in designing the modelization of the text.

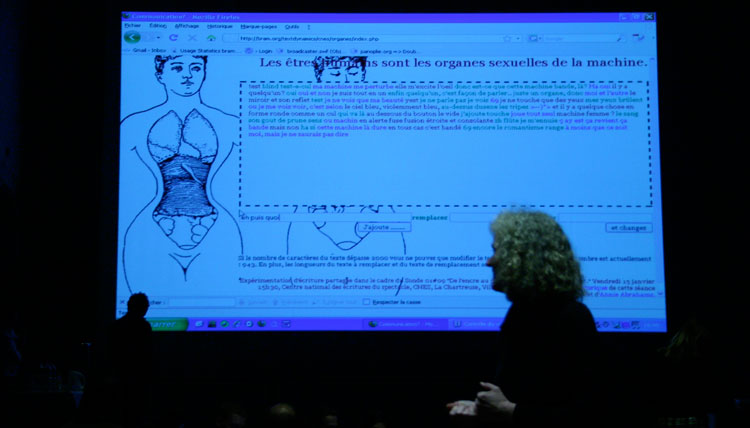

Poèmes de Marc Hodges à Gilberte. Traitement numérique des images de Jean-Blaise Évequoz : Gilberte. Générateur automatique : Jean-Pierre Balpe. Photo: D.R.

Isn’t writing from a generator implicitly recognizing that writing media and writing machines determine the content?

There has ALWAYS been a relationship between writing technologies and content. Oral poetry is not written poetry, literature before the book doesn’t follow the same criteria as after the book, and the relative standardization of book formats strongly influences their content. So, writing with a generator simply follows this general rule, and the main goal is not to make it obvious, even if, obviously, it’s also the case.

Some MIT students developed SCIgen, a generator of Computer Science research papers that can be submitted to conferences, in the spirit of the Sokal affair. Have you been attracted to the art of forgery and spoofing, a practice that is rampant on the Internet ?

No, that’s not what I’m interested in…

When you write a blog for a hyperfiction (La Disparition du Général Proust), are you not both author and character?

Hyperfiction is made for the Web, a space of constant games of hiding and exhibitionism, where none of these are contradictory. I thought it would be interesting to play with that aspect by using all the technical possibilities of the Web: characters with their own Facebook pages or blogs, constant references among themselves, ambiguities between real and fictitious biographies, advertising spoofs, links to other sites outside the hyperfiction, employing both real and modified images, etc. I am therefore the author of the whole set-up and one of the possible characters who bears my name, which doesn’t mean that it’s really me. Not any more in this case than the personal investment that every « classic » author puts into his characters (Flaubert, Mme Bovary, c’est moi…, etc). I am always playing with the notion of identity as it is rendered operational on the Internet. We know that Facebook tries to combat false identities, that it hasn’t succeeded and that meanwhile it archives all the data. It would be interesting to know what percentage of this data is fictitious. I believe that « role-playing games » take up a lot of that space.

For La Disparition du Général Proust, you asked a few artists (Nicolas Frespech, Grégory Chatonsky…) to participate. Do you also welcome writing from people on the Internet who are unknown to you?

There’s a bit of everything in this hyperfiction, which modestly tries to imagine a literature specific to the chaotic and multipolar space of the Internet, including welcoming voluntary or involuntary outside suggestions. The poems of Marc Hodges to Gilberte, for exemple, were based on drawings by Jean-Blaise Évequoz which underwent digital treatment that was beyond his control. From the moment you upload anything to the Internet, it becomes a common object that is subject to a form of collective intelligence and creativity. This is precisely why the notion of « property » is inadequate.

Poèmes de Marc Hodges à Gilberte. Traitement numérique des images de Jean-Blaise Évequoz : Gilberte. Générateur automatique : Jean-Pierre Balpe. Photo: D.R.

Aren’t you afraid that these blogs will disappear along with the companies that host them? What solutions have you found for the preservation of your texts?

We are mortal, and I don’t have the pretension of believing that my literary lucubrations will be any exception. In fact, some of the sites that I created have already disappeared; you can find traces of these disappearances on other sites. Disappearing on the Internet is strange, because what has disappeared on one site can somehow turn up on others. I’ve already noticed this several times concerning my own work. I am deeply materialistic, and if I’m interested in generativity, it’s for the particular possibility of eternity that it allows. My generators should continue to produce beyond my death if someone activates them somewhere. For this reason, I haven’t searched for any solution to archive my texts that is less important than archiving the generators. But I also know that the Institut national de l’audiovisuel (INA) and the National Library of France continuously archive a certain number of sites. Perhaps I’m already among them…

Advertisements appear, does that bother you?

They are part of this space, and I’m allowed to play with them too.

You’re planning to work with Grégory Chatonsky in creating a drama generator that will give directions to the actors. What form will this generator take? Will it be more author or more director…?

Why do you want to assign specific roles? What’s interesting about the computer model is precisely being able to mix, transform, shift the roles. I already did this type of show at the Maison de la Poésie in 2010, or before with the Palindrome dance company. What interests me in this case is to see how I can play on the actor-author-computer ambiguities. So the generator will be everything at once…

Do you agree with those who claim that the Internet will produce as many great changes in literature and the arts (I’m thinking especially of the performing arts) as the invention of print?

Yes, of course… and we’re only at the beginnning.

Emmanuel Guez

published in MCD #76, “Writing Machines”, march/may 2012

1648. Here we are in the pirate world of Stéphane Beauverger’s Le Déchronologue (1). François Le Vasseur, a former privateer turned governor of Turtle Island, is literally obsessed by these maravillas yanked from the future: true-to-nature geographic maps, turntables, electric lamps, radio transmitters and other tubes of cinchona. Henri Villon, a freebooter whose ship expels from its own century the temporal interferences of fleets from other eras, offers the autocrat a poisoned gift: a book from future times to bear witness to the destiny of the illustrious characters who will make Caribbean history and where we duly find François Le Vasseur, governor of Tortuga since 1640, along with the year, place, day and manner of his death. Fatal consequence: after a night of mental suffering faced with the inevitable announcement by ink on paper, the candidate shoots himself in the head, finally relieved to have invented a different demise from the one history had promised him.

1648. Here we are in the pirate world of Stéphane Beauverger’s Le Déchronologue (1). François Le Vasseur, a former privateer turned governor of Turtle Island, is literally obsessed by these maravillas yanked from the future: true-to-nature geographic maps, turntables, electric lamps, radio transmitters and other tubes of cinchona. Henri Villon, a freebooter whose ship expels from its own century the temporal interferences of fleets from other eras, offers the autocrat a poisoned gift: a book from future times to bear witness to the destiny of the illustrious characters who will make Caribbean history and where we duly find François Le Vasseur, governor of Tortuga since 1640, along with the year, place, day and manner of his death. Fatal consequence: after a night of mental suffering faced with the inevitable announcement by ink on paper, the candidate shoots himself in the head, finally relieved to have invented a different demise from the one history had promised him.

In a way, the patchworked YouTube collage matches that scene in the second novel of Michael Moorcock’s trilogy The Dancers at the End of Time, where a dandy from the distant future and musket-toting extraterrestrials raise havoc in London, in the Café Royal frequented by H.G. Wells at the end of the 19th century. As B-literature for fantasy or science-fiction series, the uchronia doesn’t try to revolutionize the form of the printed text itself in the now legendary manner of a Raymond Queneau or experimentations by Oulipo. Of course, we do find nice ideas, like these excerpts of more or less invented novels which seem to live their own lives in bold type at the heart of Jasper Fforde’s The Eyre Affair (4). But the double-page blank that suddenly interrupts the original edition of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, following an offense to fiction, is staged, not at the heart of the book… but on Jasper Fforde’s website!

In a way, the patchworked YouTube collage matches that scene in the second novel of Michael Moorcock’s trilogy The Dancers at the End of Time, where a dandy from the distant future and musket-toting extraterrestrials raise havoc in London, in the Café Royal frequented by H.G. Wells at the end of the 19th century. As B-literature for fantasy or science-fiction series, the uchronia doesn’t try to revolutionize the form of the printed text itself in the now legendary manner of a Raymond Queneau or experimentations by Oulipo. Of course, we do find nice ideas, like these excerpts of more or less invented novels which seem to live their own lives in bold type at the heart of Jasper Fforde’s The Eyre Affair (4). But the double-page blank that suddenly interrupts the original edition of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, following an offense to fiction, is staged, not at the heart of the book… but on Jasper Fforde’s website!