Hope for Africa

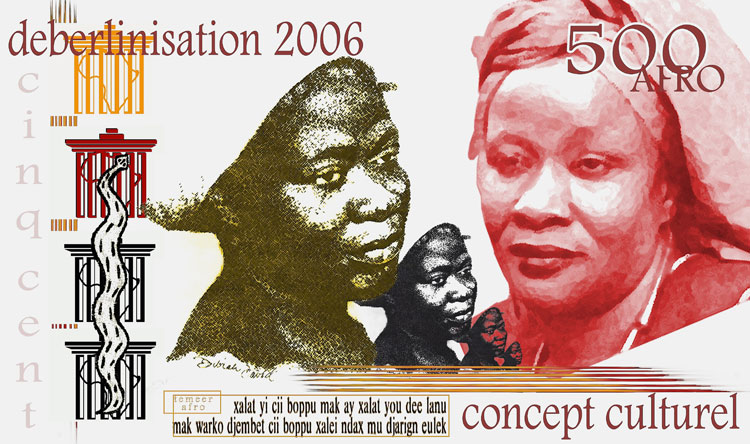

Since 2002, Mansour Ciss Kanakassy from Senegal and Baruch Gottlieb from Canada have been nurturing a concrete artistic utopia: the Afro, a unique currency for the African continent. Materialized on bills featuring Léopold Sédar Senghor and promoting an economic pan-Africanism, it shares a common goal with the Déberlinisation laboratory, which criticizes the African borders established by Berlin at the end of the 19th century. From Berlin, the two artists answered our questions (by e-mail).

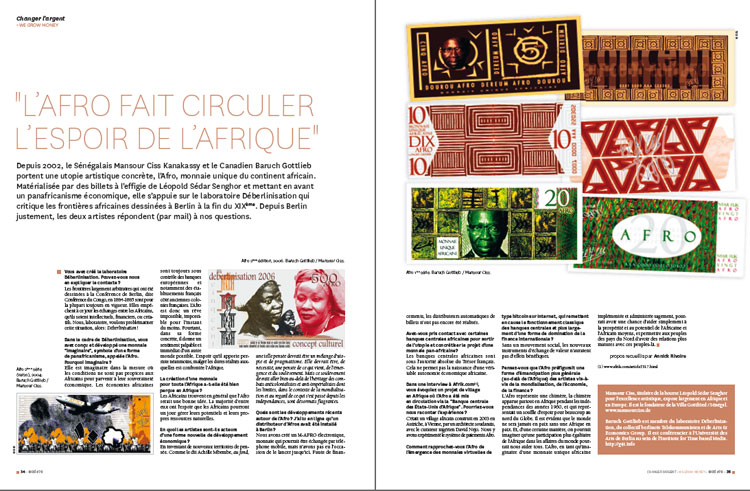

Afro 2ème série (verso), 2004. Baruch Gottlieb / Mansour Ciss. Photo: D.R.

Could you explain the context in which you founded the Déberlinisation laboratory?

The mostly arbitrary borders that were established at the Berlin Conference, or Congo Conference, in 1884-1885 are more or less still in place. To this day, they prevent exchange among Africans, whether it’s on an intellectual, financial or creative level. As a laboratory, we want to troubleshoot this situation, so: “Déberlinisation”!

For Déberlinisation, you designed and developed an “imaginary” currency as a symbol of pan-Africanism called the Afro. Why imaginary?

It’s imaginary in that current conditions are not favorable for Africans to achieve economic sovereignty. African economies are always under the control of European banks, especially French banks for the former French colonies. The Afro is an impossible dream, at least for now. However, in its concrete form, it gives people an immediate and tangible feeling of another possible world. The hope that it brings persists, despite the harsh realities that Africa faces.

Was creating a common currency for all of Africa well received in Africa

In general, Africans find that the Afro would be a good idea. The majority of Africans hope to one day manage their own potentials and natural resources.

How are artists actively involved in a new form of economic development?

By inventing new territories of thought. As Achille Mbembe says: “deep down, such a thought should be a mixture of utopia and pragmatism. It should be, by necessity, a thought of what is to come, of emergence and uprising. But this uprising should go well beyond our heritage of anticolonialist and anti-imperialist battles, whose limits, in the context of globalization and in view of what has happened since our independences, are now obvious.”

Afro 2ème édition, 2006. Baruch Gottlieb / Mansour Ciss. Photo: D.R.

What are the Afro’s recent developments? I read online that an Afro distributor was installed in Berlin?

We created M-AFRO, an electronic currency that could be exchanged via cell phone, but so far we haven’t had the chance to launch it. We currently lack the financing to make ATMs to distribute bills.

Have you contacted any central African banks in order to move from utopia to the concrete project of a pan-African currency?

Central African banks are under the absolute authority of the French Treasury. This prevents us from creating a truly autonomous African economy.

In an interview on Afrik.com (1), you talked about an African village where the Afro was circulated by the “Central Bank of the United States of Africa”. Could you tell us more about this experiment?

It was an African village conceived in 2003 in Vienna, Austria, by a Sudanese architect, along with the curator David Nejo. We experimented with an Afro payment system there.

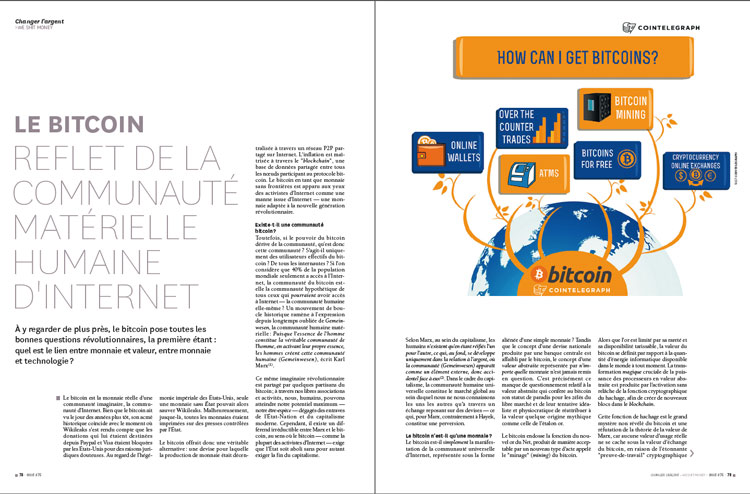

How do you relate the Afro to the emergence of virtual online currencies such as bitcoin, which challenge the conventional role of central banks and more generally the dominance of international finance?

Without a social movement to accompany them, new instruments for exchanging value would have no beneficial effects.

Do you think that the Afro prefigures a more general form of artist emancipation (beyond Africa) from globalization, economics, finance?

The Afro represents a chimera, the chimera that appeared everywhere in Africa during the independences of the 1960s, and that represented a breath of hope for many in the northern hemisphere. It’s evident that the world will never be at peace without a peaceful Africa. To a certain extent, we can imagine that Africa’s more egalitarian participation in world affairs could help us all. The Afro, as the fantasy of a unique African currency that is implemented and wisely administrated, could simply aid the prosperity and potential of average Africans, and allow countries in the North to have more mature relationships with these communities.

Interview by Annick Rivoire

published in MCD #76, “Changer l’argent”, déc. 2014 / févr. 2015

(1) http://www.afrik.com/article7317.html

Mansour Ciss, recipient of the Léopold Sédar Senghor grant for artistic excellence, exhibits widely in Africa and in Europe. He is the founder of the Villa Gottfried / Sénégal. http://mansourciss.de

Baruch Gottlieb is a member of the Déberlinisation laboratory, the Berlin collective Telekommunisten and the Arts & Economics Group. He is a lecturer at the Institute of Time-Based Media, University of Art in Berlin. http://g4t.info