“We literally heard hospitals calling for help”

> français

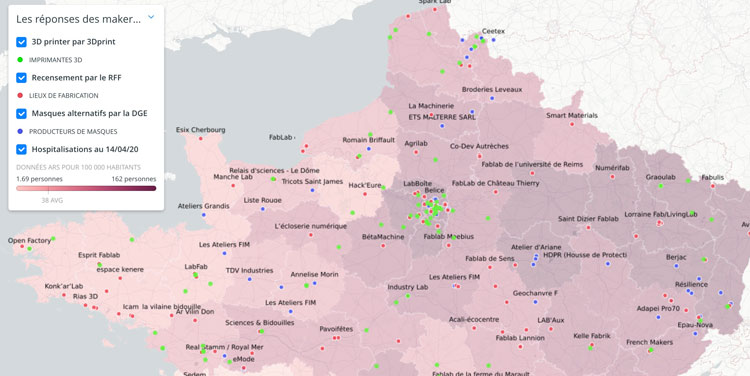

Makery relays voices from fabrication spaces federated around the collective Makers x Covid Paris. They tell the story of how they mobilized and organized to support the city’s frontline workers most exposed to the Covid-19 virus. After publishing exclusive photos of the preparation and delivery process of protective gear, Makery collected comments from the pivotal Parisians who immediately responded to the crisis by pooling their energy, skills and resources to form the collective Makers x Covid Paris.

Volunteers assemble face shields at Woma in Paris. Photo : © Quentin Chevrier

Micro-factory for urban fabrication

In Paris, the beginning of the health crisis and subsequent lockdown was met with a flurry of initiatives, followed by some frustration: how to contribute, which collective to join, which tools to use to collectively organize, how to identify material needs or respond to requests from health care workers—all while staying at home.

“We didn’t want to initiate another movement that would simply add to the confusion for those who wanted to get involved. But given the urgency of the situation, we first created our own shared file for coordination, while waiting for a larger coordinated effort. (…) After witnessing the friction caused by issues of governance and representation, we felt it was important that it have a new, neutral name: makerscovid.paris.” (Quentin Perchais, Woma)

“This common platform for exchanging information and organizing ourselves, at first very informally (through phone calls) then more structured online (shared spreadsheet, Slack server, forms, website), allowed us to really coordinate the production activities of the various members of the network. Not only did it save us time and energy, it enabled us to respond directly to the urgent requests coming from local hospitals and other organizations.” (Antonin Fournier, SimplonLab)

Mon atelier en ville – busy hands at work. Photo : © Quentin Chevrier

“It started with a group of close colleagues from Volumes, Woma and Ars Longa. Then the first labs—Atelier des amis, Mon atelier en ville and Electrolab—contributed part of their operations to our shared spreadsheet. Eventually, as requests increased from Paris City Hall, the Salvation Army and others, the collective grew to 20 fabrication spaces responding to requests and coordinating our actions. (…) We finally set up a micro website to centralize all the information regarding requests, participants and donations.” (Quentin Perchais, Woma)

The extensive and urgent need for equipment rallied all the actors around a face shield model that was easy to produce and assemble: the “Folded” design by Aruna Ratnayake at Volumes, laser cut and validated by Kremlin-Bicêtre Hospital. The various labs involved all recognized the invaluable role of rapid inter-structural coordination in optimizing parts of their work (managing requests, supplying materials, delivery), which in turn allowed the makers to focus on production—essentially of face shields and masks.

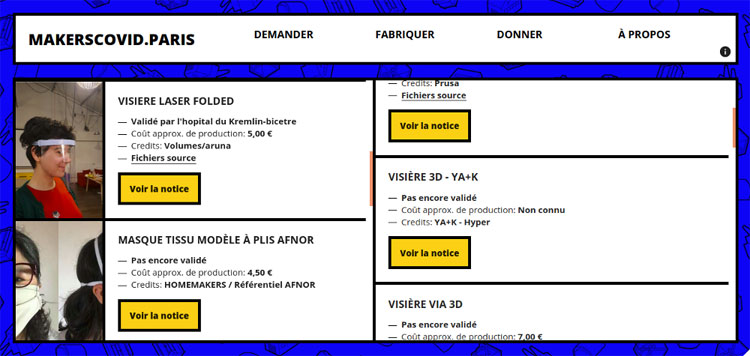

List of equipment in production on makerscovid.paris. Photo: D.R.

Solidary mesh of flexible workshops

“You need sanitary equipment, you want to place an order, or you want more information” offers the Demander (request) menu option of the makerscovid.paris online platform, which lists items in production (face shields, cloth masks, protective gown, door hook, V26 mask valve adapter…) and in development.

Homemakers, a fablab specialized in textiles and design, immediately made their digital fabrication machines available for the production of face shields, before turning to the heart of their craft: textile production. Julia (president of Homemakers) and Gilles Bessard du Parc (full-time volunteer) reflect on the beginning of their involvement.

“Homemakers joined the Makers against Covid movement on March 30. As we were worried about our families and shocked to see the number of deaths rising each day, we quickly aligned our production and connected with our fablab network, as well as our families, friends and neighbors on social media. We got into touch with Minh (Fab City Grand Paris) and were immediately integrated into the coordinated fabrication of sanitary equipment.

Gilles and Antoine assemble face shields at Homemakers. Photo : © Julia Lim – Homemakers

“We started by producing parts for face shields (3D printing and laser cutting), then we refocused on making cloth masks. Given our expertise in textiles and after studying the models provided by AFNOR, we soon led the textiles team in producing masks. Now we have 15 volunteers working on site in shifts and about 40 volunteers working remotely. We are extremely grateful to them and thank our silent heros who mobilized along with us.” (Homemakers)

Minh Man Nguyen is president of the association Fab City Grand Paris, whose goal is to develop/facilitate/localize production capacity in greater Paris.

“In an emergency response to the health crisis, Paris City Hall ordered 2,000 face shields from Fab City Grand Paris. The order was contracted and honored in less than a week thanks to a mesh of flexible workshops capable of mass production. Nearly 14,000 face shields were produced and distributed in the past two weeks, which proves that fablabs and makerspaces can adapt to fulfill an order much more efficiently than the industry ».

« Third-spaces are not only production spaces, they also serve as relay points for citizen-makers who print and assemble in their own homes, providing materials and logistics. Our association helped to centralize purchasing (made possible by advanced funds and donations), sourcing of raw materials through partnerships and the logistical flow of materials.” (Minh Man Nguyen, Fab City Grand Paris)

Marie-Valentine makes cloth masks at Homemakers. Photo : © Julia Lim – Homemakers

Reinventing the production chain

Antonin Fournier, fabmanager of SimplonLab (fablab of the company Simplon), talks about the coordination efforts both among organizations within Makers X Covid Paris, as well as internally, in order to successfully produce all the equipment ordered within very short timeframes.

“The first days were crazy, there were so many parameters we had to take into account: the materials and their availability at eventual suppliers, the various open source prototypes and their validity, priority of incoming requests, internal organization of fablabs in order to produce safely, financing the purchase of materials, etc. »

In just a few days, our fablab was transformed into a little neighborhood factory, hosting a dozen people from different backgrounds (mutual help groups on Facebook, fashion schools, community associations…). Those who come almost every day now master the chains of production from start to finish and can help initiate newcomers.” (Antonin Fournier, SimplonLab)

Baptiste Doublet Degremont is a textile designer and artist in residence at SimplonLab: “Setting up a production network during a health crisis isn’t easy. But it’s what we did with SimplonLab, where I’m (in normal times) an artist in residence. We did this because we literally heard the hospitals calling for help. Because if we don’t do it, who will?” (Baptiste Doublet Degremont, SimplonLab)

Many different skills contributed to this solidary chain of production. Carton Plein mobilized alongside the numerous Parisian fablabs and makers to pick up the face shields produced in the workshops and redistribute them “by the sheer force of our shins, on our two-carriers and cargo bikes” to hospitals, testing centers, nursing homes, clinics, etc.

Marie Boussard, fabmanager of Villette Makerz, mobilized the tools of her makerspace and offered her own knowledge and experience to produce face shields. Marie is also a designer-illustrator, who created illustrations for the makerscovid.paris website, posters and flyers. Makers x Covid Paris: “Communicating about our actions helps collect donations in order to buy more raw materials and therefore to produce—we’ve come full circle!”

SimplonLab volunteers begin working on the production of protective gowns. Photo : © Quentin Chevrier

As requests persist, questions remain

While the members of Makers x Covid Paris have successfully seized the opportunity to respond effectively to the crisis (urgency, solidary momentum, fast and efficient coordination, intelligent stock management), many questions remain regarding the post-covid cohesion of this spontaneous collective.

“What should the future city be in order to face other crises, or to have the capacity to prevent them? How can we make production sustainable while guaranteeing a certain degree of quality and remaining financially viable?” asks Minh Man Nguyen. The question of mid- to long-term cooperation is on everyone’s mind. “The challenge will be to successfully maintain this dynamic cooperation beyond the pandemic, in order to retain the network’s proven ‘strike force’.” (Antonin Fournier, SimplonLab)

“For several years, we’ve been working to cooperate among fabrication spaces. But in just two weeks, we’ve accomplished so much more as a collective than we ever did before! My hope is to be truly useful, to carry out distributed production, to have different labs talking to each other, and our next challenge: to find the conditions to cooperate!” (Quentin Perchais, Woma)

The mobilization continues.

Catherine Lenoble

published in partnership with Makery.info

Makers x Covid Paris platform and call for donations