We don’t read a book the same way our ancestors read a papyrus scroll. Reading formats demand specific usages and influence our relationship with the written text. While images dominate and print can no longer keep up with the accelerated pace of this 21st century, the issues surrounding the digitization of books are more relevant than ever.

Photo: D.R.

The history of writing and reading is linked to the history of formats. Ever since the first text was made available in digital format by Michael Hart at the University of Illinois on July 4, 1971, we have entered the period of e-incunabula. In 1970, at the Palo Alto Research Center, Alan Kay conceptualized the Dynabook, the ancestor of portable computers, which he imagined at the time as an e-reader. Nicholas Sheridon and the Xerox team designed the first rewritable electronic paper, the Gyricon. By the 1990s, a new kind of e-paper was developed in the laboratories of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by Joseph Jacobson, cofounder of E-Ink Corporation, acquired by the Taiwanese company Prime View International in December 2009.

New reading interfaces

Ever since we entered the 21st century, there has been no doubt that we are transitioning from five centuries of print publishing to digital publishing. The new reading devices representative of this mutation can be classified into four families, presented briefly in the order in which they have impacted our usage. We should consider them as interfaces between the content and the readers, and distinguish the evolution of screens from that of paper.

First, office computers and laptops, destined to be replaced by touchscreen tablets and cloud computing: As mobile computing is on the rise, the permanence of desktop computers in homes, then in offices, is doubtful. Next, dedicated e-readers, of which the first was commercialized under the name Librié in Japan in April 2004 by Sony: Their use of e-ink technology, with no backlight, reproduces the effects of ink on paper, thus offering the same reading comfort as print. Then smartphones, among which the first to have had an impact on reading was the Apple iPhone in 2007. Finally, touchscreen tablets, which since 2009 have changed our relationship to reading through books enhanced with videos and multiple animations, driving an emerging generation of pure-player publishers.

E-paper, which is starting to be produced in rolls like paper, with color and video, has a bright future ahead. But screens, such as Oled, are also making progress. For example, Sony has used OTFT (Organic Thin-Film Transistors) technology to develop prototypes of rollable video screens. Has the codex book been nothing more than a parenthesis between papyrus scrolls and rolls of Oled e-paper?

New reading pratices

Backlit or not, these devices still pose the human problems of ergonomy and affordability. They don’t elicit spontaneous usage as e-readers. Actually, they are often multi-purpose. But what was the visible relationship in usage between a clay tablet and a papyrus scroll?

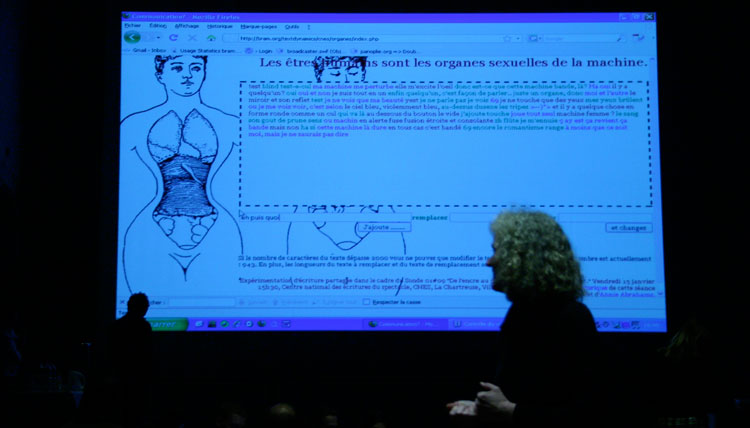

With connected devices offering a single rewritable surface, the notion of page disappears. The number of pages no longer has any real meaning. It tends to be replaced by the estimated reading time. Reading becomes more fragmented, hypertextual, less linear and more extensive—as well as more and more social, along with the development of social networks, blogs and wikis. Lastly, it becomes more and more nomadic and therefore connected, in the cloud, or even streaming on demand, like listening to music.

Photo: D.R.

The mere fact that print is not hypertextual is enough to condemn it. Readers of the 21st century want content that is more and more customizable, updated in real time, geolocalized and participative.

Enormous stakes

This mutation of formats, this transition from « book » as object to services linked to reading, is all part of our computing reality, while it impacts our writing practices. The gradual loss of handwriting in favor of software applications can just as well liberate our creativity as lead us to a Fahrenheit 451 situation.

The destiny of books and reading today seems to be in the hands of the online and entertainment industries. Amazon. Google. Apple. The crucial question now is whether digital culture can still be enough of a counterweight so that new reading devices can be emancipating, just as print was, beginning in the 16th century.

The stakes are indeed enormous. The novel was undoubtedly linked to the codex format. Today, new narrative forms are starting to emerge with transmedia. In this model, the same fiction is simultaneously developed on various platforms (e-readers, smartphones, connected TVs, game consoles, etc), with platform-specific content exploiting the particular merits of each one. Each format then becomes a different entry point that immerses readers even deeper into the story.

By modifying our reading and writing practices, these new formats also modify our capacity for cognition and memorization, as well as our vision of the world. Our changing worldview is particularly unstable, as digital territories invite us to reconsider reading beyond the book.

With the metamorphosis of books as containers and their volatility as contents, we must imagine reading interfaces for the end of this century, at the confluence of the Internet of things, augmented reality and artificial intelligence—a mentor-book, of which science-fiction author Neal Stephenson was perhaps the prophet in The Diamond Age.

Lorenzo Soccavo

published in MCD #76, “Writing Machines”, march/may 2012

Lorenzo Soccavo is an independent researcher of books and publishing in Paris. He is the author of Gutenberg 2.0, le futur du livre (M21 éditions, 2008) and the essay De la bibliothèque à la bibliosphère (2011, digital edition published by NumérikLivres and in print by Morey éditions). He regularly speaks about the issues and challenges of digitizing books, as a teacher and a lecturer. Blog: http://ple-consulting.blogspot.com

Nous voici dans l’univers pirate du Déchronologue de Stéphane Beauverger (1). François Le Vasseur, corsaire devenu gouverneur de l’Ile de la Tortue, est littéralement obsédé par ces maravillas arrachées au futur : cartes géographiques plus vraies que nature, platines, lampes électriques, émetteurs radio et autres tubes de quinquina. Henri Villon, flibustier dont le navire repousse hors de son siècle les ingérences temporelles de flottes d’autres époques, propose à l’autocrate un cadeau empoisonné : un livre venu des temps à venir pour témoigner du destin des illustres personnages qui feront l’histoire caraïbe et où figure, en bonne place, François Le Vasseur, gouverneur de Tortuga depuis l’an 1640, avec l’année, le lieu, le jour et la manière de sa mort. Conséquence fatale : après une nuit de souffrances mentales face à l’annonce de l’inéluctable par l’encre sur le papier, l’impétrant se tire une balle dans la tête, enfin soulagé de s’être inventé un autre trépas que celui que l’histoire lui avait promis.

Nous voici dans l’univers pirate du Déchronologue de Stéphane Beauverger (1). François Le Vasseur, corsaire devenu gouverneur de l’Ile de la Tortue, est littéralement obsédé par ces maravillas arrachées au futur : cartes géographiques plus vraies que nature, platines, lampes électriques, émetteurs radio et autres tubes de quinquina. Henri Villon, flibustier dont le navire repousse hors de son siècle les ingérences temporelles de flottes d’autres époques, propose à l’autocrate un cadeau empoisonné : un livre venu des temps à venir pour témoigner du destin des illustres personnages qui feront l’histoire caraïbe et où figure, en bonne place, François Le Vasseur, gouverneur de Tortuga depuis l’an 1640, avec l’année, le lieu, le jour et la manière de sa mort. Conséquence fatale : après une nuit de souffrances mentales face à l’annonce de l’inéluctable par l’encre sur le papier, l’impétrant se tire une balle dans la tête, enfin soulagé de s’être inventé un autre trépas que celui que l’histoire lui avait promis. D’une certaine façon, le collage sur YouTube rejoint par son patchwork cette scène du deuxième roman de la trilogie des Danseurs de la fin des temps de Michael Moorcock, où un dandy du futur le plus lointain et des extraterrestres à mousquets foutent le brin à Londres, dans le Café Royal fréquenté par H.G. Wells à la fin du XIXe siècle londonien. Littérature de série B pour feuilletons de fantastique ou de science-fiction, l’uchronie ne cherche pas pour autant à révolutionner la forme même du texte imprimé à la façon désormais légendaire d’un Raymond Queneau ou des expérimentations de l’Oulipo. On y trouve certes de jolies idées, comme ces extraits de romans plus ou moins inventés qui semblent vivre leur propre vie en caractère gras au cœur de L’Affaire Jane Eyre de Jasper Fforde (4). Mais la double page blanche qui rompt soudainement l’édition d’origine du roman Jane Eyre de Charlotte Brontë, suite à une infraction à la fiction, est mise en scène, non au cœur du livre… mais sur le site Internet de Jasper Fforde !

D’une certaine façon, le collage sur YouTube rejoint par son patchwork cette scène du deuxième roman de la trilogie des Danseurs de la fin des temps de Michael Moorcock, où un dandy du futur le plus lointain et des extraterrestres à mousquets foutent le brin à Londres, dans le Café Royal fréquenté par H.G. Wells à la fin du XIXe siècle londonien. Littérature de série B pour feuilletons de fantastique ou de science-fiction, l’uchronie ne cherche pas pour autant à révolutionner la forme même du texte imprimé à la façon désormais légendaire d’un Raymond Queneau ou des expérimentations de l’Oulipo. On y trouve certes de jolies idées, comme ces extraits de romans plus ou moins inventés qui semblent vivre leur propre vie en caractère gras au cœur de L’Affaire Jane Eyre de Jasper Fforde (4). Mais la double page blanche qui rompt soudainement l’édition d’origine du roman Jane Eyre de Charlotte Brontë, suite à une infraction à la fiction, est mise en scène, non au cœur du livre… mais sur le site Internet de Jasper Fforde !