Y a-t-il quelqu’un dans la machine ?

Mort en octobre dernier, Friedrich Kittler est un théoricien encore méconnu du grand public français. Son originalité est d’avoir mis en dialogue les pensées de Foucault et de Lacan avec la théorie des médias, et notamment McLuhan. Une pensée qui relève notamment que l’écriture est aujourd’hui liée au code informatique, un code néanmoins de plus en plus inaccessible à l’utilisateur.

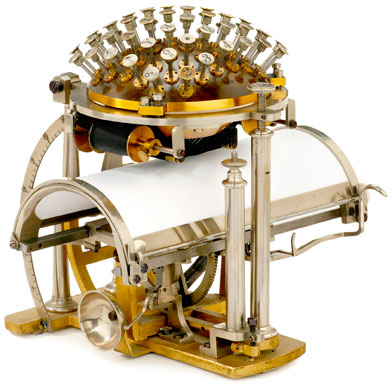

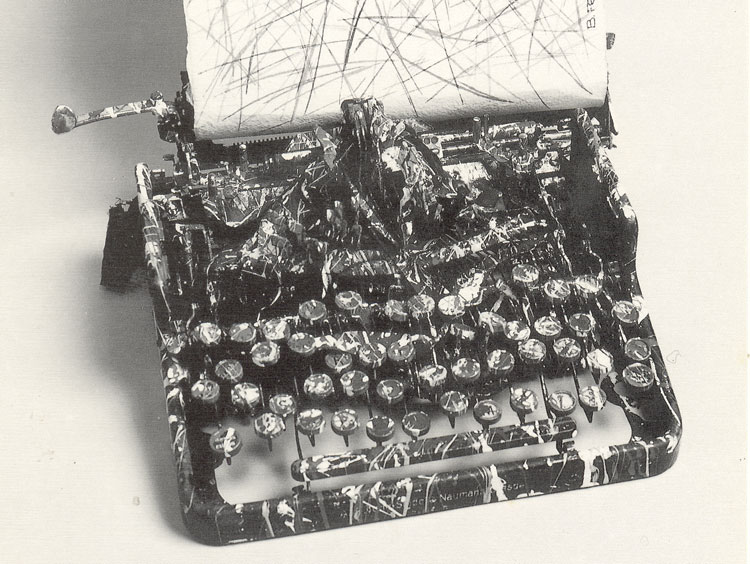

The Hansen Writing Ball,1865. Photo: D.R.

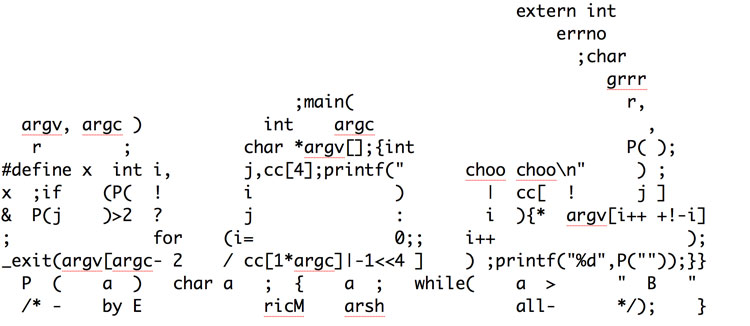

Dans une interview, le germaniste et théoricien des médias Friedrich Kittler affirmait : je ne peux pas comprendre que les gens n’apprennent à lire et à écrire que les 26 lettres de l’alphabet. Ils devraient au moins y ajouter les 10 chiffres, les intégrales et les sinus (…). Ils devraient de plus maîtriser deux langages de programmation, afin de disposer de ce qui, en ce moment, constitue la culture. Ailleurs, il fustigeait la volonté de l’industrie informatique de déposséder l’utilisateur d’ordinateur de la main mise sur sa machine.

La question a hanté le débat entre les technophiles et les technophobes : est-ce l’homme qui utilise la machine pour produire du sens ou sont-ce les machines qui produisent l’homme et ses productions ? En un mot, qui sont les maîtres et les esclaves de notre siècle numérique où l’informatique est devenu le gestionnaire omniprésent de nos activités pratiques et théoriques. Cette question a toute sa place dans la théorie des médias, mais c’est une question vaine en réalité si nous partons du constat que l’homme n’a jamais maîtrisé ses productions signifiantes, au sens où il en aurait été l’auteur pleinement conscient et autonome. Tel est le point de départ de Friedrich Kittler.

Quelle est sa thèse directrice ? Que le système d’écriture d’une époque, c’est-à-dire les techniques dont dispose une culture pour enregistrer, transmettre et traiter les informations, détermine ce que l’homme est, ce qu’il pense et la perception qu’il a de lui-même. Si l’on peut parler d’un déterminisme technique du penseur allemand, c’est néanmoins plus sous les auspices de Foucault que de Marx que Kittler a placé sa pensée. Comme son prédécesseur français, qui écrivait dans L’ordre du discours : s’il y a des choses dites, il ne faut pas en demander la raison immédiate aux choses qui s’y trouvent dites ou aux hommes qui les ont dites, mais au système de la discursivité, aux possibilités et aux impossibilités énonciatives qu’il ménage, Kittler s’attache en effet à mettre au jour les conditions de possibilité d’émergence des différents types de discours qui permettent selon les époques à des productions successives (du vol des oiseaux chez les romains aux symptômes de la névrose) de devenir signifiants pour leurs contemporains. Tout, à une époque donnée, et cela indépendamment des intentions signifiantes de ceux qui parlent, ne peut pas être dit, ni entendu. Mais là où Foucault s’intéresse exclusivement aux ordres du discours déterminant les productions langagières, Kittler élargit son champ d’investigation à l’environnement technique dans son ensemble.

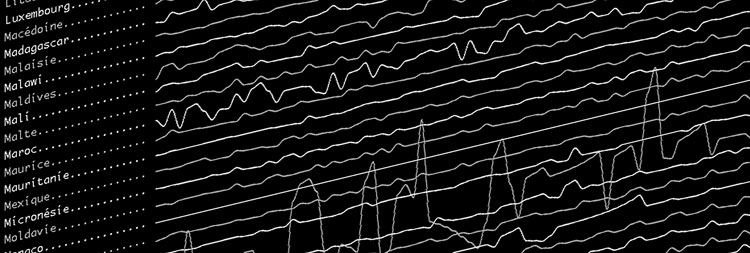

L’écriture fut le premier système technique au moyen duquel les informations furent enregistrées, transmises et traitées. Elle fut pendant un temps le seul canal du souvenir et de la constitution du monde. Son monopole fut remis en cause au début du XXème siècle par le phonographe, la photographie et le cinéma. Au-delà de la pluralité nouvelle des représentations de la réalité qu’ils offrent, ces nouveaux médias instituent une rupture en ce que, contrairement à l’écriture qui reproduit symboliquement la réalité, leur mode de représentation passe par l’enregistrement des effets physiques de la réalité et conservent ainsi la trace du corps ou de l’événement. Kittler analyse ainsi dans Grammophon, Film, Typewriter le récit de Salomo Friedlaender, Goethe parle dans le phonographe (1916) qui imagine la possibilité d’entendre de nouveau la voix de Goethe en enregistrant les vibrations de l’air que ses paroles n’ont pu manquer de produire, et qui pour certaines, renvoyées d’objets en objets, persistent encore aujourd’hui, quoique affaiblies. Le son enregistré, comme la photographie, constituerait ainsi des preuves mécaniques de l’existence de l’objet. L’écriture produit du sens par le symbole, le phonographe et la photographie par l’enregistrement.

Un système de production du sens modifié à partir de 1900.

C’est sur le système de l’enseignement qui avait institué le système d’écriture de 1800 que les nouveaux médias agissent, mettant un terme à ce que l’on peut appeler le règne de la signification. Jusqu’en 1800 en effet, c’est la voix maternelle qui en susurrant à l’oreille des enfants de tendres paroles fait parler. Entre ces syllabes et les premiers mots prononcés par les enfants, s’établit une continuité portée par une instance productrice du sens. De la même manière que la syllabe « ma » naît de l’amour mère-enfant, pour peu à peu se transformer en mot constitué « maman », la parole s’établit ainsi naturellement des syllabes établissant un lien affectif entre l’enfant et la mère aux premiers mots doués de sens.

Thomas A. Edison, Home phonograph, 1906. Photo: D.R.

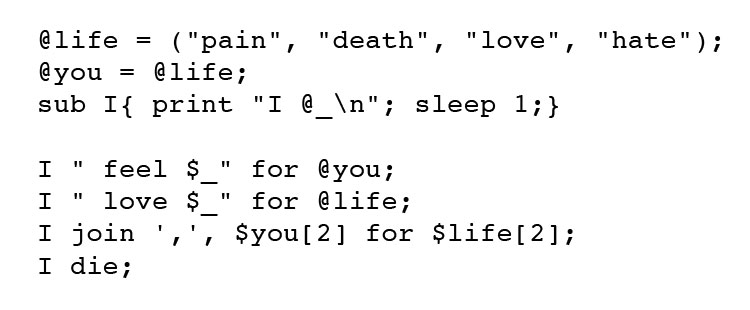

Mais le règne des nouveaux médias bouleverse les modalités de la transmission de la parole. Désormais, de la même façon que le phonographe enregistre ce que les cordes vocales émettent comme sons avant toute mise en ordre des signes et toute signification (les vibrations sont des fréquences qui se situent en deçà des seuils de perception de mouvements et qui ne peuvent être transcrites ni écrites), l’apprentissage du langage devient le traitement de données en elles-mêmes non signifiantes. Apprendre à parler et à écrire revient désormais à apprendre des syllabes dénuées de sens, que l’on combinera pour donner des mots et des phrases. La syllabe « ma » n’a plus une valeur affective particulière, mais n’est que le résultat d’une production systématique des sons à partir des lettres de l’alphabet (ma-me-mi-mo-mu…). La mémorisation ne se fait pas en un processus naturel et continu de la parole de la mère à celle de l’enfant, mais l’enfant apprend désormais de manière sérielle des syllabes dénuées de sens. Le système d’écriture de 1900 est un jeu de dés avec des unités discrètes ordonnées de façon sérielle. Voilà ce qui constituent les médias au sens moderne du terme : des matériaux de base dénués de sens, conçus par des générateurs au hasard, dont la sélection construit des ensembles.

Les discours produits ne sont plus les mêmes. Il faut selon Kittler radicaliser l’idée de Walter Benjamin selon laquelle le cinéma produit de la dispersion qui s’oppose à la concentration bourgeoise. Cela est bien plus général et plus systématique. Le film n’a pas de primauté parmi les médias qui révolutionnent l’art et la littérature. Tous produisent une fuite des idées dans le sens psychiatrique du terme. Le théoricien relate ainsi dans Das Aufschreibesystem les expérimentations du psychiatre viennois Stransky (1905). Ses sujets d’expérimentations, parmi lesquels des collègues et des patients, doivent parler une minute dans le tube du phonographe (si possible vite et beaucoup). Les mêmes comportements sont observés chez tous : sont prononcées des phrases ne se souciant plus de signifier. Le phonographe produit des réponses provocatrices, qu’aucun serviteur de l’État ou pédagogue ayant une certaine considération de soi aurait pu écrire. Des individus qui doivent parler ou lire plus vite qu’ils ne pensent déclarent nécessairement une petite guerre à la discipline.

Il s’agit d’un changement de paradigme qui affecte encore aujourd’hui la production du sens. Il n’y a à partir de 1900 plus d’instance productrice de discours qui transformerait les débuts inarticulés en significations, mais un processus aléatoire d’enregistrement et de combinaison.

Quelle place occupe la révolution numérique dans ce système ?

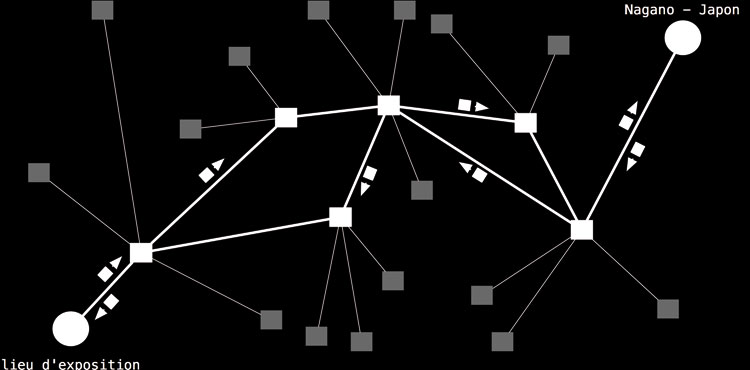

L’apparition de l’ordinateur n’a fait qu’accomplir le caractère non signifiant des éléments discrets dont la combinaison produit des énoncés signifiants. Avec le codage binaire, les flux de données acoustiques, optiques et écrites, autrefois différenciés et autonomes, sont aujourd’hui codés par les mêmes éléments de base et transmis par les mêmes fibres optiques. Au monopole de l’écriture a succédé le monopole des chiffres, alors même que le lien avec la réalité que le phonographe et la photographie avaient institué par rapport à l’écriture a été rompu, puisque la reproduction ne se fait plus par enregistrement mais par codage. Sons et images, voix et textes ne sont plus que des interfaces produites par une série de chiffres. La différence entre les médias n’est plus qu’un effet de surface et non l’expression d’une différence réelle.

Corollairement, le niveau technique de production du sens (le code) n’est pas celui sémantique d’existence de la signification. Kittler insiste sur l’écart entre le code, de plus en plus inaccessible à l’utilisateur, et les interfaces, et souligne les efforts de l’industrie informatique pour restreindre les possibilités d’intervention sur la machine, transformant la machine en outil prêt à l’emploi qu’elle n’est pas. Pour ce faire, les possibilités d’intervention sur la machine et de modification de ses paramètres techniques sont restreints, en même temps que les velléités de l’utilisateur de le faire sont canalisés par le fait que les interfaces soient d’usage facile et immédiat, ce qui dispense de toute intervention.

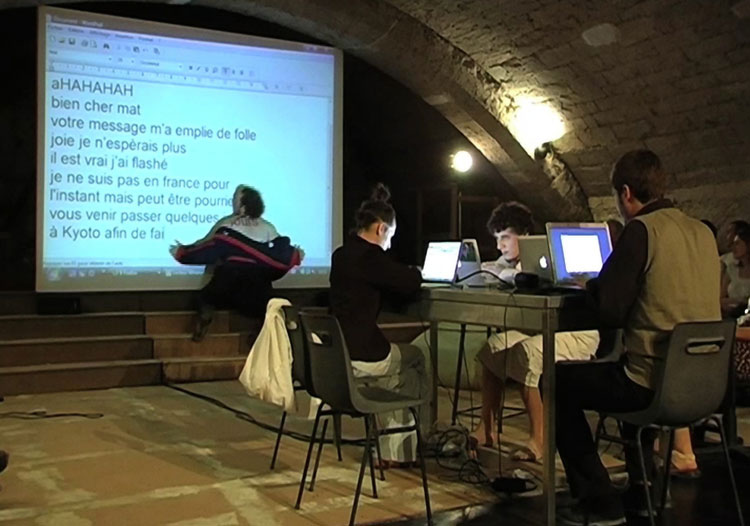

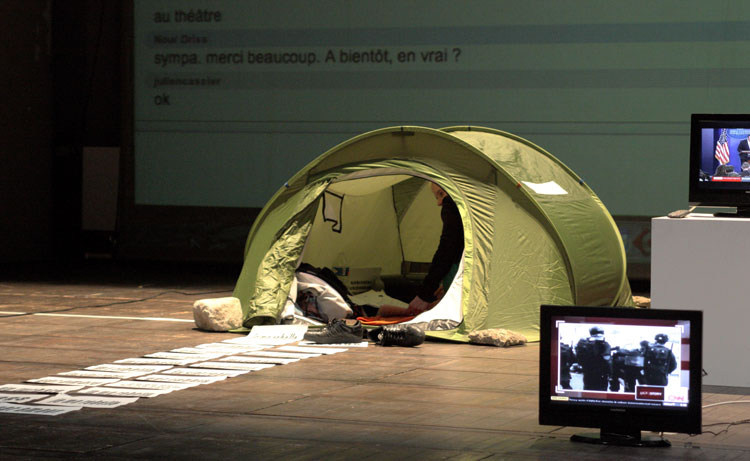

Ainsi, si l’homme n’a jamais maîtrisé ses productions signifiantes, comme nous le disions en préambule, si celles-ci sont aujourd’hui déterminées par le système binaire d’écriture qui est le nôtre, l’ère numérique nous conduit en sus à nous demander s’il y a un auteur dans la machine, c’est-à-dire si et comment l’utilisateur peut, au sein de ces déterminations, se réapproprier une intention signifiante.

Frédérique Vargoz

agrégée de philosophie

publié dans MCD #66, « Machines d’écritures », mars / mai 2012

To wrap up, a word on QR (Quick Response) codes, those two-dimensional bar codes that pop up everywhere, on all kinds of ads and political campaign posters. QR (under free license) can be read by any last-generation mobile phone. Encapsulating texts, sounds and images, QR are a new format and a new medium for poets who love to play with the material aspects of writing. Putting a poem into a QR is playing with your own invisibility. In France, there have been a few rare attempts of varying interest (by Stéphane Bataillon, for example). With his background in graphic design, the American artist Peter Ciccariello takes the game farther by placing a QR (containing a poem and a first image) into a second image, which is generated by a computer. Facinated by the relationship between words and images, Ciccariello produces visual artworks that usually include poems which have become almost unreadable in linear form, as a result of their insertion in sophisticated collages esthetically reminiscent of the 1980s and ’90s. In QR Poem, the artist reiterates Mallarmé’s gesture of randomness, generating poems that are decrypted and de(QR-)coded rather than interpreted… Or how, with a roll of the dice, to write a poem using technology that was initially designed to manage your stocks!

To wrap up, a word on QR (Quick Response) codes, those two-dimensional bar codes that pop up everywhere, on all kinds of ads and political campaign posters. QR (under free license) can be read by any last-generation mobile phone. Encapsulating texts, sounds and images, QR are a new format and a new medium for poets who love to play with the material aspects of writing. Putting a poem into a QR is playing with your own invisibility. In France, there have been a few rare attempts of varying interest (by Stéphane Bataillon, for example). With his background in graphic design, the American artist Peter Ciccariello takes the game farther by placing a QR (containing a poem and a first image) into a second image, which is generated by a computer. Facinated by the relationship between words and images, Ciccariello produces visual artworks that usually include poems which have become almost unreadable in linear form, as a result of their insertion in sophisticated collages esthetically reminiscent of the 1980s and ’90s. In QR Poem, the artist reiterates Mallarmé’s gesture of randomness, generating poems that are decrypted and de(QR-)coded rather than interpreted… Or how, with a roll of the dice, to write a poem using technology that was initially designed to manage your stocks!